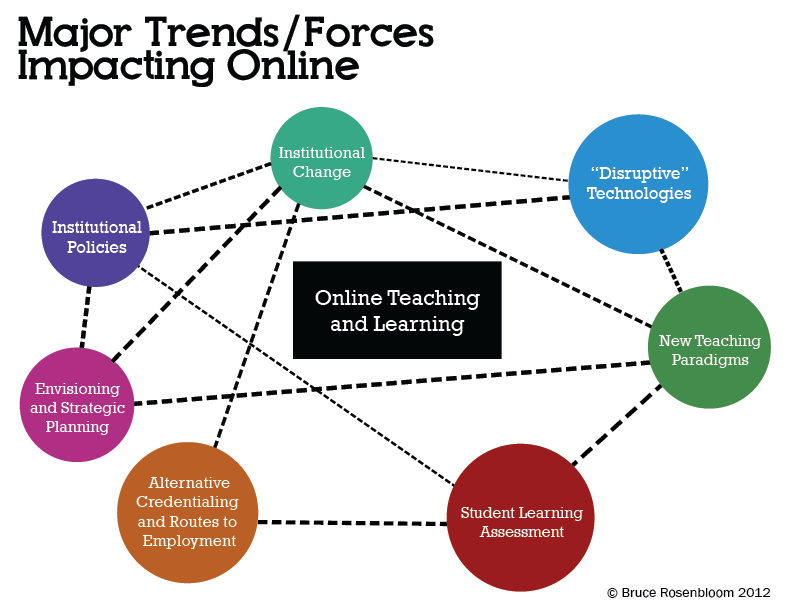

I have been assiduously following the field of online teaching /learning for many years. Online learning has been, I would argue, the biggest trend in higher education in the past decade. From an early growth rate of 20% per annum (according to the Sloan-C Reports), to a current level of around 10% per annum growth, online learning has been a force to be reckoned with. In the latest Babson study of online, fully 75% of college Chief Academic Officers regard online as being strategically important to their institutions. Moreover, online (and its cousin hybrid learning), have produced changes in teaching on campus across the landscape, including:

- The Flipped Classroom–where content is delivered online and outside the classroom, while engaging activities happen within the classroom;

- A re-examination of the lecture as the primary mode of teaching (closely related to the flipped classroom trend);

- A boon to older, non-traditional students returning to college for whom “the campus experience” is not needed and for whom the convenience of online is paramount for degree completion;

- The gradual dis-aggregation of the faculty role (see previous post) in which essential parts of what constitutes a professor’s work are getting farmed out to others including course design, grading, and teaching;

- A rise in collaborations between private content providers, tech companies and colleges to seize a competitive advantage for their online programs; and

- A gradual shift in the role of the professor from “sage on stage” to a facilitator/guide of learning.

Online teaching has been a force for change and arguably, the major force in higher education in this last decade. This is noteworthy since higher education has by and large been an entity resistant to change. But there is change, and there is transformative change. I would agree with Clayton Christensen’s term, “disruptive technology” when assessing the impact of online in higher education. Indeed, online learning, as stated above, has already caused significant change in the delivery of college courses, but not fundamental change in the prevailing “instructional paradigm” as described by Tagg in the “The Learning Paradigm College.” The “online revolution” has hardly produced systemic change at most colleges, only incremental change at best.

What Hasn’t Changed?

In the latest Inside Higher Ed edition, I was reading a stimulating blog post entitled “The Right Path to MOOC Credit,” by Pamela Tate. The author was skeptical about whether Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) would transform higher education as some have argued. Ms. Tate writes, “Dig deeper and we are left to ask how many MOOC courses will really be worth college credit, where will the credits be accepted, and for how long wil college credits even be the primary measure of learning?” So despite the potential for such an innovation as MOOCs, in reality, it has yet to transform the academy in any substantial ways.

When I consider what a transformation would entail, John Tagg’s “The Learning Paradigm College” would be a starting point. He points to five characteristics of this new learning paradigm including:

- Supporting students in pursuing their own goals

- Requiring frequent student performances

- Providing frequent and ongoing feedback

- Assuring a long time- horizon for learning, and

- Providing for stable communities of practice.

Traditional teaching structures that Tagg references often have little to do with actual student learning, and often are detrimental to learning. These practices include:

- Course-credit hours to measure achievement,

- The 15 -week semester,

- “Atomized” curriculums that simple do not add up to a whole,

- Assessment via grades that provides little context or proof of learning,

- Discipline/department structures that don’t reflect newer societal inter-relationships,

- Tenure and promotion policies that often don’t reward good teaching, and

- Isolated classrooms and students walled-off from each other and the outside world. These and other attributes reduce the chances of any transformative change beyond token or marginalized reforms. In a future blog post I will examine these further.

It is evident that traditional structures within the academy have not been transformed by developments in online learning, or more generally, instructional technologies. At best, I believe that technology innovation has improved learning and student engagement to a degree and at worst, it functions as a band-aide for deficient pedagogy and institutional structures. So, although many faculty within these institutions (K-12 included) do their best to teach students, we all labor under an instructional paradigm that can accept innovations to teaching, but are still largely impervious to transformative change.

References

Christensen, Clayton M. & Overdorf, Michael, (2000). “Meeting the Challenge of Disruptive Change” Harvard Business Review, March–April 2000.

Tagg, John, (2003). The Learning Paradigm College, Jossey Bass, San Francisco, CA.

Tate, Pamela, “The Right Path to MOOC Credit,” Inside Higher Ed, February 14, 2013. Retrieved from: http://www.insidehighered.com/views/2013/02/14/course-course-approval-moocs-may-not-be-wise-essay