Last week’s (August 7, 2011) article in the Chronicle of Higher Education entitled, “Professors Cede Grading Power to Outsiders—Even Computers” triggered a very visceral reaction in me. While I have been an advocate of hybrid/online learning at my institution, and have been following the field closely for over a decade, I too easily dismissed faculty resistance to online learning as reactive and ill-informed. With this piece of the puzzle coming into focus, I starting to see that the traditional professor as we know him or her, may have good reason to resist new technological encroachments into their turf, for the future of the professoriate may become what I term, “the disaggregated professor.”

The Chronicle article (a must-read for all in higher education) explains how the Western Governors University “hired 300 adjunct professors to do nothing but grade student work.” Grade inflation was a significant issue at that university and administrators felt that by not having direct contact with students (even in an online context) that hired evaluators would be more objective and stem the rising tide of grades. To tweak the noses of traditional professors even more, that institution and the University of Central Florida have gone further in this process and have computerized grading of exams via programmable software. A pedagogue might rightly ask, “Is nothing sacred, not even assessment?”

The pros and cons of this “outsourcing of assessment” is not the point of this post. Surely promoters can point to cost savings, faster assessment turnaround, and purported objectivity, while skeptics would decry the lack of the human factor and that faculty expertise in the subject area creates better student assessment and feedback. Of more interest me is the larger picture as I see it — the disaggregation of the traditional professor’s role into discrete and separable parts.

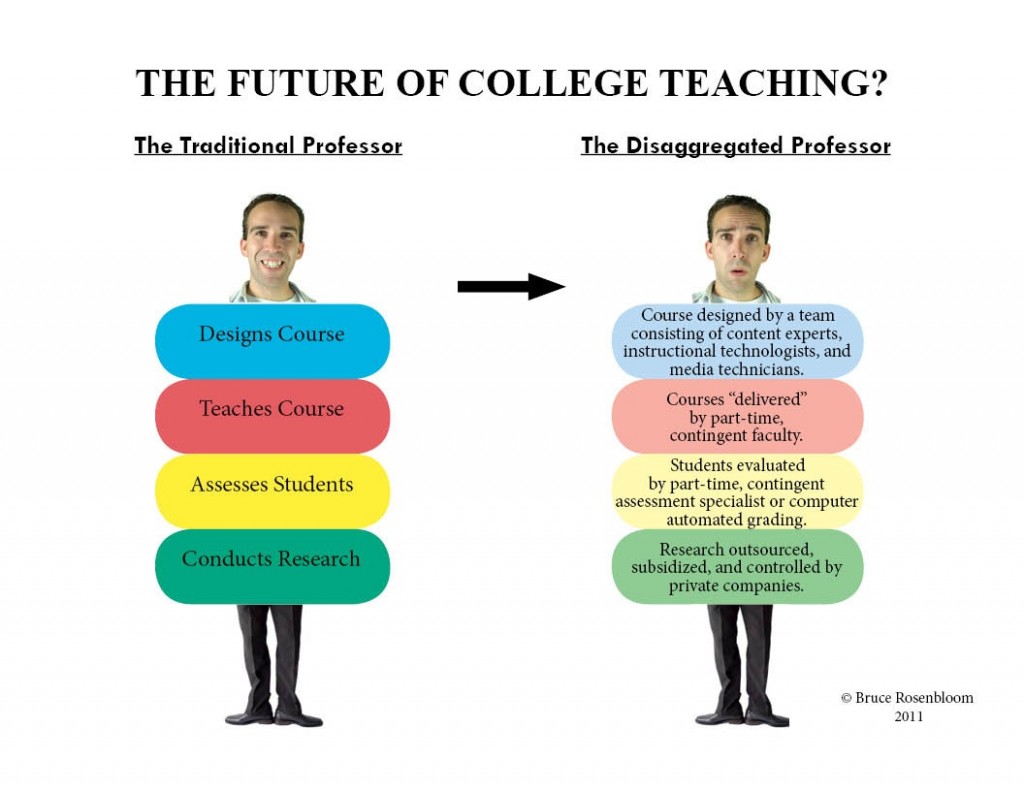

As the above diagram illustrates, it is not merely assessment that is being removed from the exclusive realm of the professoriate, but other critical aspects of the role of “the traditional professor.” The University of Phoenix and other for-profit online institutions have employed a unique model whereby course creation and design is performed by a team of content experts, instructional technologists and media specialists. The rationale behind this model is that such a team is more likely to produce excellent courses, since specialists cover only their area of expertise, whereas your average professor cannot be expected to be an expert designer and media producer. It should be noted that other models exist that enable faculty to still be at the center of course design. Such models include campus support from campus technologists and media specialists, and another model whereby an educational publisher creates course modules and content. Regardless of the model, college professors are being challenged as never before regarding the creation and design of their courses.

As the above diagram illustrates, it is not merely assessment that is being removed from the exclusive realm of the professoriate, but other critical aspects of the role of “the traditional professor.” The University of Phoenix and other for-profit online institutions have employed a unique model whereby course creation and design is performed by a team of content experts, instructional technologists and media specialists. The rationale behind this model is that such a team is more likely to produce excellent courses, since specialists cover only their area of expertise, whereas your average professor cannot be expected to be an expert designer and media producer. It should be noted that other models exist that enable faculty to still be at the center of course design. Such models include campus support from campus technologists and media specialists, and another model whereby an educational publisher creates course modules and content. Regardless of the model, college professors are being challenged as never before regarding the creation and design of their courses.

Once courses are created, many institutions employ course instructors to teach pre-designed and pre-packaged content. So rather than having full-time faculty teach the course, the course would be “delivered” by contingent faculty. In this case, the online world is reflecting what is happening on college campuses throughout the U.S.; namely, the rise of adjunct faculty to teach a significant part of the college curriculum. Adjunct faculty as a percentage of newly hired faculty has been increasing at a steady pace for several decades with an ever-increasing percentage of college courses being taught by adjuncts.

“With increasing frequency, colleges have hired part-time and full-time contingent faculty members, often poorly paid—who now make up 49 and 20 percent of the professoriate, respectively. Their growing presence represents a trend that threatens to render moot the heated debate over tenure.”

(Source: Miller, Margaret, A., “More Pressure on faculty members from every direction,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, August 22, 2010, p 1.)

However, in the traditional model, even adjuncts are often given a significant role in regards to structuring their courses. They will have less input into course design in the “disaggregated model” of the future to one where adjuncts become mere “course deliverers.”

With course design, teaching, and student assessment being taken away from professors, you would think that it couldn’t get any worse for the future of the traditional professor. You’d be wrong on that assumption. One of the primary functions of the professoriate is publication and research. Both research and publication are critical to tenure, promotion and faculty advancement. However, with the trend toward less tenured professor being appointed, and the move on many campuses to adjunct and 3-5 year faculty contracts, this area seems to be ripe for change.

Although this is more speculative than the previous sections, I believe that business and industry will co-opt and control much of the potentially marketable research now being done on campuses. This trend was hinted at in two Chronicle of Higher Education articles, “States Push Public Universities to Commercialize Research” (March 29, 2002) and “Public Research Universities Get Advice From Industry: Please Your Patrons” (February 20, 2011). Both articles point to increased pressure on the part of publicly funded universities to form alliances with the business sector. These partnerships often come with many strings attached, including that publication of the research results will take a back seat to the potential commercialization of those results. In many instances, researchers were either prevented from publishing their results in order for their business partner to gain a competitive advantage, or coerced to skew the research data or alter content. Invariably, such partnerships decrease the control professors have over both the subject and method of their research as well as the dissemination of the results. It sees reasonable to forecast that professors will have less control over such research in the future. Looming on the horizon, but rarely acknowledged in academia, is the real prospect of outsourcing this commercialized research to lower-cost countries. I feel this trend is inevitable, and bodes ill for U.S. higher education generally.

In conclusion, college administrations are looking increasingly to strategies that will likely negatively impact professors. The thrust to find cost-savings and be operationally efficient and flexible, point to a “disaggregated” future for the U.S. professoriate. Faculty resistance may slow down, but not prevent, this trend. We are in the midst of a major paradigm shift concerning the role of college professors in teaching and learning.

Note: Fulya Olgac, Graphic Designer for “The Future of College Teaching” image.