Note: For the sake of brevity, the term “online” used in this post and the survey described, includes hybrid or blended teaching in addition to fully online courses. The distinction between “hybrid” and “online” concerns the extent to which a course has some face to face component; online has 0-20% classroom teaching, hybrid has between 30 and 80%.

Background

As part of my interest in online learning within CUNY, in the Fall of 2011 I proposed conducting a CUNY-wide survey concerning planning and implementation for online teaching. My main intent with this project was to get a measure of online development at CUNY’s 20+ campuses since I felt there were common issues among all CUNY schools regarding online teaching that needed to be researched, presented and discussed.

Among the issues of interest to me include:

- Who on campus is involved with online planning?

- Is there a strategic plan for online?

- What is the current extent of online teaching?

- What are the major implementation issues for online?

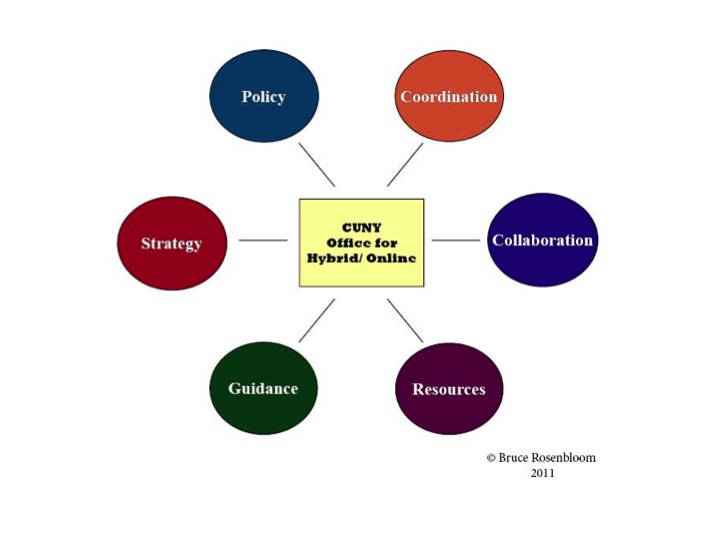

- What, if any, policy areas needed to be addressed?

- What are recommendations for future action?

With the approval of Dr. George Otte, CUNY’s Director of Technology, and the cooperation of the CUNY Committee on Academic Technology (CAT), I was given permission to proceed with the survey. The CAT committee and other colleagues vetted the survey prior to distribution. Individuals identified as the “point person” on their campus most responsible for hybrid/online planning and implementation were asked to complete the survey. Of the 22 campuses or professional schools surveyed, 18 responded to the survey, which, I believe, makes it fairly representative of the state of online learning within CUNY at that point in time.

The Panel Discussion

On December 1, 2011, findings from the survey were presented in a panel discussion at CUNY’s 10th Annual Technology Conference at John Jay College. The panel discussion entitled, “Strategic Planning for Online: Potential for CUNY Campuses,” included myself, Bruce Rosenbloom (City College), Janey Flanagan (Borough of Manhattan Community College) and Michelle Fraboni (Queens College). The survey results were reviewed and each panelist had a chance to comment on the findings. Questions were then fielded from the audience, and an engaging discussion ensued.

The Survey consisted of 24 questions covering a range of planning and implementation issues concerning online learning. I believe this process was a concrete step toward examining current online practices with an eye toward re-envisioning strategies critical to online success at CUNY campuses.

Note: Subsequent blog posts in the near future will detail specific results from the survey and my recommendations based on survey results.

Additional Resources:

A. I have created a screen capture file that provides a more extensive overview of the panel discussion and considerations regarding the survey. Moreover, I address the need for the survey and review some of the preliminary slides from my conference presentation.

Overview of Survey and Panel (14 minutes)

http://www.screencast.com/t/nnirCt3LwKa

B. Conference Program Description (from 10th Annual CUNY IT Conference)

______________________________________________________

Strategic Planning for Online: Potential for CUNY Campuses

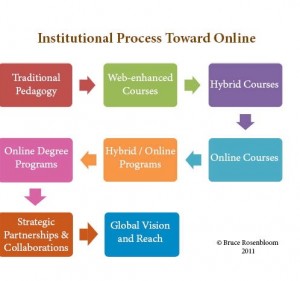

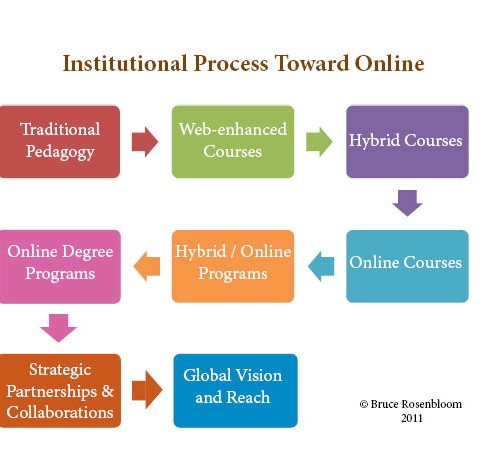

Online teaching at CUNY is undergoing a transition, from early ad-hoc approaches to one whereby campus administrators and faculty are determining more focused, structured approaches for hybrid/online activities on their campuses. A recent CUNY-wide survey of campus administrators was conducted to delineate online strategies, policies and practices. Findings from this survey will be interwoven with insights from panelists to better stimulate a dialogue on achieving the potential for online teaching and learning throughout CUNY.

Janey Flanagan, Director of E-Learning, Borough of Manhattan Community College

Michelle Fraboni, Lecturer, Elementary & Early Childhood Education / Online Teaching Initiative Coordinator, CETL, Queens College

Bruce Rosenbloom, Director, Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning, City College, Online Learning Coordinator-Title V, City College, Adjunct Professor, CUNY Online BA Program

View PowerPoint Slides

_______________________________________________________

(Source: Converge Online; Website: http://www.convergemag.com/events/CUNY-IT-Conference-2011.html

C. Survey Questions: PDF File:

Survey_CUNY_Online_Learning